Western corn rootworm 抗性

Field-Evolved Resistance to Bt Maize by Western Corn Rootworm

Aaron J.Gassmann*,Jennifer L.Petzold-Maxwell,Ryan S.Keweshan,Mike W.Dunbar

Department of Entomology,Iowa State University,Ames,Iowa,United States of America

Abstract

Background:Crops engineered to produce insecticidal toxins derived from the bacterium Bacillus thuringiensis(Bt)are planted on millions of hectares annually,reducing the use of conventional insecticides and suppressing pests.However,the evolution of resistance could cut short these benefits.A primary pest targeted by Bt maize in the United States is the western corn rootworm Diabrotica virgifera virgifera(Coleoptera:Chrysomelidae).

Methodology/Principal Findings:We report that fields identified by farmers as having severe rootworm feeding injury to Bt maize contained populations of western corn rootworm that displayed significantly higher survival on Cry3Bb1maize in laboratory bioassays than did western corn rootworm from fields not associated with such feeding injury.In all cases,fields experiencing severe rootworm feeding contained Cry3Bb1maize.Interviews with farmers indicated that Cry3Bb1maize had been grown in those fields for at least three consecutive years.There was a significant positive correlation between the number of years Cry3Bb1maize had been grown in a field and the survival of rootworm populations on Cry3Bb1maize in bioassays.However,there was no significant correlation among populations for survival on Cry34/35Ab1maize and Cry3Bb1maize,suggesting a lack of cross resistance between these Bt toxins.

Conclusions/Significance:This is the first report of field-evolved resistance to a Bt toxin by the western corn rootworm and by any species of Coleoptera.Insufficient planting of refuges and non-recessive inheritance of resistance may have contributed to resistance.These results suggest that improvements in resistance management and a more integrated approach to the use of Bt crops may be necessary.

Citation:Gassmann AJ,Petzold-Maxwell JL,Keweshan RS,Dunbar MW(2011)Field-Evolved Resistance to Bt Maize by Western Corn Rootworm.PLoS ONE6(7): e22629.doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0022629

Editor:Peter Meyer,University of Leeds,United Kingdom

Received April20,2011;Accepted June27,2011;Published July29,2011

Copyright:?2011Gassmann et al.This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License,which permits unrestricted use,distribution,and reproduction in any medium,provided the original author and source are credited.

Funding:This research was supported through the Biotechnology Risk Assessment Grant program of the United States Department of Agriculture,and through the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences at Iowa State University.The funders had no role in study design,data collection and analysis,decision to publish,or preparation of the manuscript.

Competing Interests:Aaron Gassmann has received research funding,not related to this project,from Dow,Monsanto,Pioneer,Syngenta,and Bayer CropScience.Aaron Gassmann has filed a provisional patent for the seedling based assay described in this manuscript.This does not alter the authors’adherence to all the PLoS ONE policies on sharing data and materials.

*E-mail:aaronjg@https://www.sodocs.net/doc/a54018399.html,

Introduction

Transgenic crops engineered to produce insecticidal toxins derived from the bacterium Bacillus thuringiensis(Bt)were planted on more than58million hectares worldwide in2010[1]. Benefits of Bt crops include reduced use of harmful insecticides and regional suppression of some key agricultural pests [2,3,4,5,6].Within the United States,and worldwide,more area is planted to Bt maize Zea mays L.than any other Bt crop [1].The western corn rootworm Diabrotica virgifera virgifera LeConte(Coleoptera:Chrysomelidae)is among the most serious pests of maize within the United States,with larval feeding on maize roots causing the majority of crop losses from this pest [7].Beginning in2003,Bt maize was commercialized for control of western corn rootworm larvae and was rapidly adopted by farmers,constituting over45%of maize crop in the United States during2009[8,9].However,the evolution of resistance by the western corn rootworm could cut short the benefits of Bt maize.

The refuge strategy is used in the United States and elsewhere to delay pest resistance to Bt crops[10].This strategy uses non-Bt host plants as a refuge for Bt susceptible genotypes.Mating of homozygous susceptible pests with pests that are homozygous for Bt resistance produces progeny that are heterozygous for resistance traits.The delay in resistance expected under the refuge strategy becomes greater as the dominance of resistance decreases and is greatest when resistance is completely recessive[11].Thus, as the area planted to refuge decreases or resistance becomes more dominant,pests are predicted to evolve resistance more quickly [11,12].

The western corn rootworm has repeatedly demonstrated its ability to adapt to pest management strategies[7].Examples include the evolution of resistance to conventional insecticides and the cultural practice of crop rotation[13,14,15].The widespread planting of Bt maize targeting western corn rootworm raised concerns that this pest would evolve resistance to Bt.Of additional concern are data suggesting that resistance of western corn rootworm to Bt maize is not recessive[16].Furthermore,a lack of compliance in planting of refuges has been documented among farmers that grow Bt maize in the United States[17].Both of these factors are expected to increase the risk of western corn rootworm evolving Bt resistance.

In the present study,we compared populations of western corn rootworm that were sampled from two types of maize fields: problem fields and control fields.Farmers reported severe feeding injury by corn rootworm to Bt maize in problem fields but not in control fields planted to Bt or non-Bt maize.We report that western corn rootworm populations sampled from problem fields showed statistically significant,but not complete,resistance to the Bt maize.Resistance was found only for Cry3Bb1maize,the type of Bt maize that had been grown historically in those fields,and was not present for maize that produced Bt toxin Cry34/35Ab1. Our results represent the first case of field-evolved resistance by the western corn rootworm to Bt maize and the first case of field-evolved resistance by a coleopteran to Bt toxin,as all previous cases of field-evolved resistance have involved Lepidoptera[18]. Methods

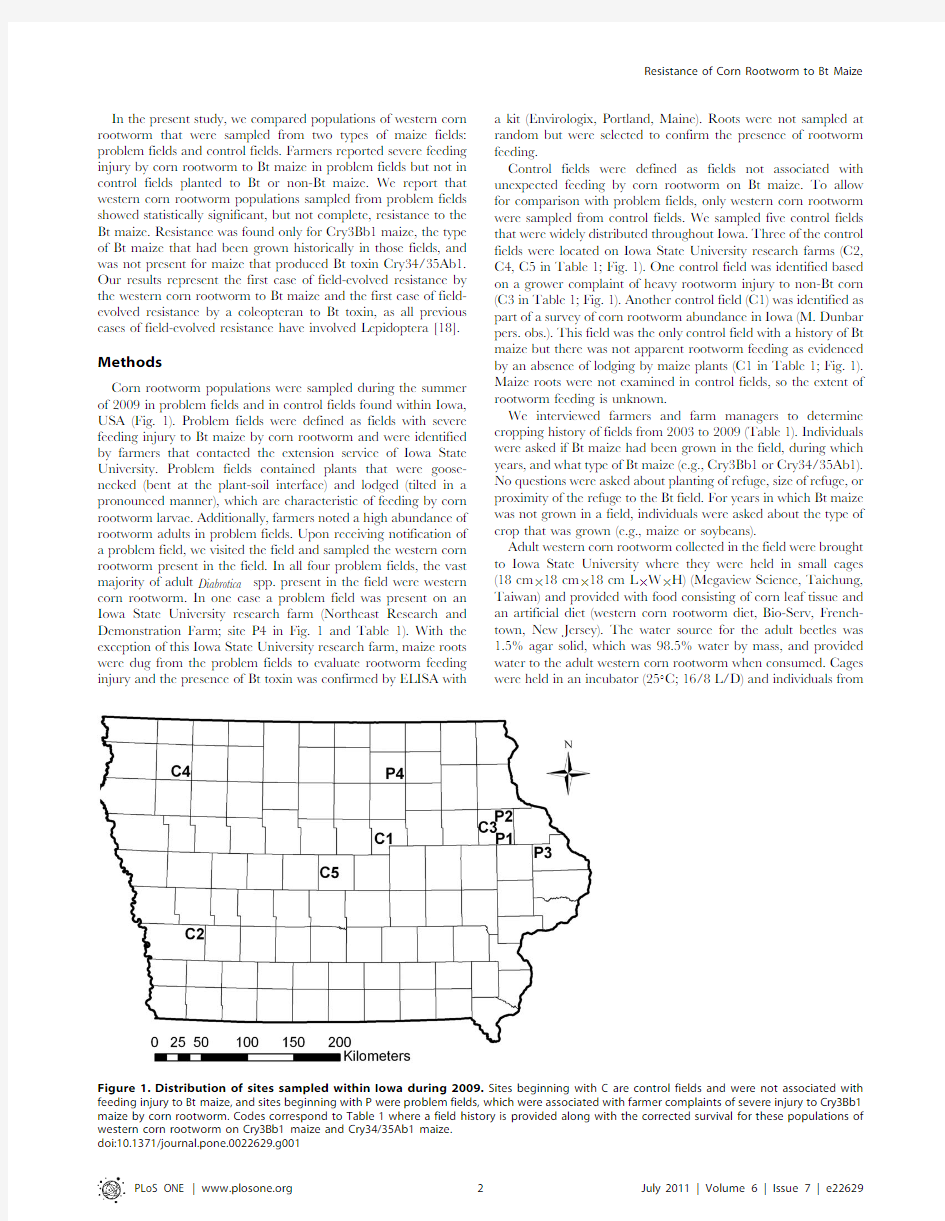

Corn rootworm populations were sampled during the summer of2009in problem fields and in control fields found within Iowa, USA(Fig.1).Problem fields were defined as fields with severe feeding injury to Bt maize by corn rootworm and were identified by farmers that contacted the extension service of Iowa State University.Problem fields contained plants that were goose-necked(bent at the plant-soil interface)and lodged(tilted in a pronounced manner),which are characteristic of feeding by corn rootworm larvae.Additionally,farmers noted a high abundance of rootworm adults in problem fields.Upon receiving notification of a problem field,we visited the field and sampled the western corn rootworm present in the field.In all four problem fields,the vast majority of adult Diabrotica spp.present in the field were western corn rootworm.In one case a problem field was present on an Iowa State University research farm(Northeast Research and Demonstration Farm;site P4in Fig.1and Table1).With the exception of this Iowa State University research farm,maize roots were dug from the problem fields to evaluate rootworm feeding injury and the presence of Bt toxin was confirmed by ELISA with a kit(Envirologix,Portland,Maine).Roots were not sampled at random but were selected to confirm the presence of rootworm feeding.

Control fields were defined as fields not associated with unexpected feeding by corn rootworm on Bt maize.To allow for comparison with problem fields,only western corn rootworm were sampled from control fields.We sampled five control fields that were widely distributed throughout Iowa.Three of the control fields were located on Iowa State University research farms(C2, C4,C5in Table1;Fig.1).One control field was identified based on a grower complaint of heavy rootworm injury to non-Bt corn (C3in Table1;Fig.1).Another control field(C1)was identified as part of a survey of corn rootworm abundance in Iowa(M.Dunbar pers.obs.).This field was the only control field with a history of Bt maize but there was not apparent rootworm feeding as evidenced by an absence of lodging by maize plants(C1in Table1;Fig.1). Maize roots were not examined in control fields,so the extent of rootworm feeding is unknown.

We interviewed farmers and farm managers to determine cropping history of fields from2003to2009(Table1).Individuals were asked if Bt maize had been grown in the field,during which years,and what type of Bt maize(e.g.,Cry3Bb1or Cry34/35Ab1). No questions were asked about planting of refuge,size of refuge,or proximity of the refuge to the Bt field.For years in which Bt maize was not grown in a field,individuals were asked about the type of crop that was grown(e.g.,maize or soybeans).

Adult western corn rootworm collected in the field were brought to Iowa State University where they were held in small cages (18cm618cm618cm L6W6H)(Megaview Science,Taichung, Taiwan)and provided with food consisting of corn leaf tissue and an artificial diet(western corn rootworm diet,Bio-Serv,French-town,New Jersey).The water source for the adult beetles was 1.5%agar solid,which was98.5%water by mass,and provided water to the adult western corn rootworm when consumed.Cages were held in an incubator(25u C;16/8L/D)and individuals

from Figure1.Distribution of sites sampled within Iowa during2009.Sites beginning with C are control fields and were not associated with feeding injury to Bt maize,and sites beginning with P were problem fields,which were associated with farmer complaints of severe injury to Cry3Bb1 maize by corn rootworm.Codes correspond to Table1where a field history is provided along with the corrected survival for these populations of western corn rootworm on Cry3Bb1maize and Cry34/35Ab1maize.

doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0022629.g001

each population were housed in separate cages.Adults were provided with an oviposition substrate that consisted of moist, finely sieved soil(,180m m)placed in a10cm Petri dish.Eggs obtained from each population were placed separately in45mL plastic cups containing moistened sieved soil,and then sealed in a plastic bag and placed in a cold room at8u C for at least5months to break diapause.Following exposure to cold,eggs were stored for one week at25u C.Eggs were washed from the soil using a screen with250m m openings and then placed atop moistened sieved soil held in a10cm Petri dish.Neonate larvae began hatching approximately one week thereafter.

Neonate larvae from each population were evaluated in laboratory bioassays for their survival on two transgenic maize hybrids,each of which contained a unique Bt toxin targeting corn rootworm.One hybrid(DeKalb DKC6169)produced Cry3Bb1. The other hybrid(Mycogen2T789)produced Cry34/35Ab1.For both of these hybrids,we also evaluated rootworm survival on a near isogenic hybrid that lacked a gene for a rootworm active Bt toxin but otherwise was genetically similar to its respective Bt hybrid.In the case of Cry3Bb1maize,the non-Bt hybrid was DKC6172(DeKalb)and for Cry34/35Ab1maize the non-Bt hybrid was2T777(Mycogen).

Maize plants used in bioassays were grown in a greenhouse (25u C,16/8L/D)in1L containers made of clear plastic (Reynolds Food Packaging,Shepherdsville,Kentucky)with supplemental lighting provided with400W high-pressure sodium bulbs(Ruud Lighting Inc.,Racine,Wisconsin).Containers were filled with750mL of a1:1ratio of Sunshine Sun Gro SB300and Sunshine Sun Gro LC1potting soils(Sun Gro Horticulture Canada Ltd.,Vancouver,British Columbia).Seeds were planted one per container at a depth of ca.4cm.Beginning two weeks after planting,plants were fertilized weekly with100mL of Peters Excel15-5-15Cal-Mag Special(Everris International,Gelder-malsen,The Netherlands)at a concentration of4mg per mL. Maize seeds of2T789and2T777were coated with a seed treatment(CruiserMaxx250,Syngenta,Basel,Switzerland),which contained the neonicotinoid insecticide Thiamethoxam.Prior to planting,this seed treatment was removed by washing ca.50seeds in a solution of1mL dish detergent(Ultra Palmolive Original, Colgate-Palmolive Company,New York,New York)and250mL deionized water.Seeds were placed in the detergent solution for20 minutes and agitated gently using a stirring plate and magnetic stirring bar.This process was repeated three times with seeds rinsed four times with deionized water between each time they were washed.Seeds were then rinsed four times and allowed to dry for approximately12hours,followed by one hour of soaking in a 10%bleach solution,during which they were stirred every15 minutes.After seeds were removed from the bleach solution,they were rinsed10times with deionized water and then allowed to dry for at least24hours.This process removed virtually all visible signs of the seed treatment.Insecticidal seed treatment was not applied to DKC6169and DKC6172.However,to ensure that no residual insecticide was present,seeds were bleached following the methods used with2T789and2T777.

Plants were grown in a greenhouse for three to four weeks,until they contained at least five fully formed leaves(V5stage),and then moved to incubators for bioassays.For bioassays,plants were first trimmed to a height of20cm to allow for storage in incubators. Two to three leaves were left on each plant but were trimmed to 8cm long.Recently hatched larvae(less than24hours old)were removed from the soil’s surface within their Petri dish using a fine brush and placed at the base of a maize plant on a root that had been exposed by moving away a small amount of soil.Maize plants remained in their original1L containers throughout the bioassay.Between10and20neonates were placed on the base of each https://www.sodocs.net/doc/a54018399.html,rvae were distributed equally between Bt and non-Bt maize plants.Cups containing plants and larvae were placed in an incubator for17days(25u C,65%RH,16/8L/D),and plants were watered as needed.

After17days,the aboveground biomass of the plant was excised and the soil,containing roots and larvae,was removed from the1 L plastic container and placed on a Berlese funnel to extract larvae from the soil.A length of17days was selected for bioassays because it allowed sufficient time for some of the fastest developing larvae to reach the third and final instar[19].Root masses were held on Berlese funnels over4days and rootworm larvae were collected in15mL glass vials containing10mL of85%ethanol. The average sample sizes per population were12.764.8(mean6 standard deviation)bioassay cups for Cry3Bb1maize and for its non-Bt counterpart,and12.864.8bioassay cups for Cry34/

Table1.Sampling date in2009,corrected survival in bioassays,and history of planting in problem fields(P1–P4)and control fields (C1–C5)from2003to2009.

Corrected Survival Field History a

Site Date Sampled Cry3Bb1Cry34/35Ab103040506070809

P111September0.61+0.100.0660.042333333

P211September0.6160.060.0360.022235555

P311September0.4960.050.1460.032222333

P414August0.4060.060.2060.102223333

Mean0.52±0.050.11±0.06

C126September0.3260.110.2560.062223333

C215September0.2160.08--------------1212122

C311September0.1760.050.1360.092222222

C423September0.1060.040.006NA1214232

C501September0.0660.040.0660.052312612

Mean0.17±0.050.11±0.06

a Field history indicates the crop that was planted in a field each year:1=soybean,2=maize lacking rootworm active Bt,3=Cry3Bb1maize,4=Cry34/35Ab1maize,

5=combination of Cry3Bb1maize and Cry34/35Ab1maize,6=research plots with non-Bt maize and several Bt maize hybrids(mCry3A[46],Cry3Bb1,and Cry34/35Ab1). doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0022629.t001

35Ab1maize and for its non-Bt counterpart.We did not have sufficient western corn rootworm eggs to test one of the populations(C2from Table1)on Cry34/35Ab1maize.

Data Analysis

Data on the number of field-years(i.e.,planting of one field for single year)during which problem fields and control fields were planted to Cry3Bb1maize were compared using a G test of independence with a Williams’s correction[20].

For each bioassay cup,proportional survival was calculated as the quotient of the number of larvae recovered after17days divided by the number of neonates initially placed in a bioassay container.The mean proportional survival for each population on each type of maize was analyzed with a two-way,mixed-model analysis of variance(ANOVA)(PROC MIXED in SAS).Data for the two types of Bt maize(Cry3Bb1maize and Cry34/35Ab1 maize)were analyzed separately.The ANOVA included the fixed factors of field type(problem field vs.control field),maize hybrid (Bt maize vs.non-Bt maize)and their interaction.Random factors in the analysis were population,which was nested within field type, and the interaction between maize hybrid and population nested within field type.Survival data were transformed by the arcsine of the square root to ensure homogeneity of variance and normality of the residuals.Pairwise contrasts were conducted using the PDIFF option in PROC MIXED.

For each population,we calculated corrected survival as the complement of corrected mortality.Corrected mortality was determined using the correction of Abbott[21],and was calculated for each population by adjusting mortality of larvae from each bioassay cup with Bt maize by the average mortality on the non-Bt near isogenic hybrid.Average corrected survival for each population was compared between control fields and problem fields for Cry3Bb1maize and for Cry34/35Ab1maize based on a one-way ANOVA(PROC ANOVA in SAS). Corrected survival also was used to test the significance of three correlations among all populations sampled.We tested for the following correlations:1)corrected survival of populations on Cry3Bb1maize and Cry34/35Ab1maize,2)corrected survival for populations on Cry3Bb1maize and the number of years populations had been exposed to Cry3Bb1maize in the field and3)corrected survival for populations on Cry34/35Ab1maize and the number of years populations had been exposed to Cry34/ 35Ab1maize in the field.Correlations were measured using a Pearson correlation coefficient and tested for significance against the null hypothesis of r=0(PROC CORR in SAS).

Results

The average level of rootworm feeding injury observed in problem fields was1.860.7nodes(mean6standard deviation; N=12)based on the Iowa State University root injury scale, which ranges from0nodes(no feeding injury)to3nodes(heavy feeding injury)[22].All roots sampled from problem fields were from maize plants that produced Cry3Bb1as indicated by ELISA. Interviews with farmers indicated that problem fields were planted to Cry3Bb1maize for at least three consecutive growing seasons while only one control field(C1)was planted to Cry3Bb1 maize for any consecutive growing seasons(Table1).Further-more,Cry3Bb1maize was planted for significantly more field-years in problem fields(14of28field-years)than in control fields (6of35field-years)(G=7.68;df=1;P=0.006).By contrast, control fields were planted to a greater diversity of crops and employed an array of management practices to control corn rootworm(Table1).For example,control fields were planted to soybeans in7of35fields-years while problem fields were not planted to soybeans in any of the28field-years.

Survival in bioassays on Cry3Bb1maize was affected by a significant interaction between field type and maize hybrid (F=7.06;df=1,7;P=0.03).On the non-Bt hybrid,survival was similar,and did not differ significantly,between populations from problem fields and control fields(P=0.74)(Fig.2A).By contrast, on Cry3Bb1maize,survival was three times higher and significantly greater for insects from problem fields than from control fields(P=0.011),indicating that insects from problem fields were resistant to Cry3Bb1maize(Fig.2A).However, survival was significantly lower on Cry3Bb1maize than on non-Bt maize for populations from problem fields(P=0.008),indicating that problem fields contained a mixture of resistant and susceptible individuals,that resistance was incomplete,or that a combination of these factors was present.Additionally,survival was significantly lower on Cry3Bb1maize compared with non-Bt maize for populations from control fields(P,0.0001).

A different pattern emerged when populations were tested against Cry34/35Ab1maize and its non-Bt near isogenic hybrid (Fig.2B).The interaction between field type and maize hybrid was not significant(F=0.07;df=1,6;P=0.80)and the effect of field type was not significant(F=0.003;df=1,6;P=0.96).An effect of hybrid was present,with populations displaying significantly lower larval survival on Cry34/35Ab1maize than non-Bt maize (F=61.48;df=1,6;P=0.0002)(Fig.2B).Survival was not significantly different between populations from problem fields and control fields on Cry34/35Ab1maize(P=0.95)or on non-Bt maize(P=0.87).These results indicate that populations were equally susceptible to Cry34/35Ab1maize,and that this Bt toxin significantly reduced survival.

A second set of complementary analyses were conducted with survival scores for larvae on Bt maize that were corrected for survival on the accompanying non-Bt near isogenic hybrid (Table1).Corrected survival was significantly higher,and three times greater,for larvae from problems fields than control fields on Cry3Bb1maize(F=20.61;df=1,7;P=0.003),which indicates that populations from problem fields were resistant to Cry3Bb1 maize.However,no difference between populations from control fields and problem fields was detected on Cry34/35Ab1maize (F,0.1;df=1,6;P=0.99).

No significant correlation occurred among populations for corrected survival of larvae on Cry3Bb1maize and Cry34/35Ab1 maize(r=0.068;df=6;P=0.87),indicating an absence of cross resistance between these Bt toxins(Fig.3A).Cry3Bb1maize had been grown for at least one field-year in seven of the nine fields sampled(Table1),and among populations there was a significant positive correlation between the number of years a field had been planted to Cry3Bb1maize and survival on Cry3Bb1maize (r=0.832;df=7;P=0.005),indicating that an increased duration of exposure to Cry3Bb1maize in the field resulted in greater resistance to this Bt toxin(Fig.3B).Cry34/Cry35Ab1maize had been grown in only three of the nine fields sampled and for a total of only one field-year alone and five field-years in combination with Cry3Bb1maize(Table1).No significant correlation was detected between frequency with which Cry34/35Ab1maize was cultivated and survival on Cry34/35Ab1maize(r=20.56;df=6; P=0.15).

Discussion

Survival of western corn rootworm on Cry3Bb1maize in laboratory bioassays was significantly higher for insects from problem fields where farmers reported severe root injury to

Cry3Bb1maize than from control fields where such injury was not reported (Fig.2A).Furthermore,there was a significant correlation between the number of years Cry3Bb1maize had been grown in a field and survival of western corn rootworm on Cry3Bb1maize (Fig.3B).These data indicate that the western corn rootworm is evolving resistance to Cry3Bb1maize in some populations in Iowa,USA.This is the first case of the western corn rootworm,or any species of beetle,evolving resistance to a Bt toxin in the field [18].Insects collected from problem fields did not display greater survival on Cry34/35Ab1maize (Fig.2B).Additionally,no correlation in survival on Cry3Bb1maize and Cry34/35Ab1maize was observed among populations,indicating an absence of cross resistance between these Bt toxins (Fig.3A).

One factor that may have contributed to the resistance observed here is that Bt maize producing Cry3Bb1is not considered a high-dose event against corn rootworm [23].High-dose events are expected to delay resistance by making the inheritance of resistance more recessive [10].Additionally,genetic analysis of a greenhouse-selected strain found that resistance to Cry3Bb1maize in western corn rootworm was not a recessive trait [16].In the context of the refuge strategy,recessive inheritance of resistance caused by high-dose events will reduce survival on Bt crops for heterozygous offspring that result from mating between insects from refuge and Bt fields,thereby delaying resistance [18,24].The ability of heterozygous resistant western corn rootworm to survive on Bt maize may have diminished the effectiveness of refuges to delay resistance [12].

A second factor that may have contributed to the evolution of resistance was insufficient refuge populations.Currently,only 50%of Bt maize planted in Midwest complies with US EPA requirements for refuge size and proximity to Bt fields [17].Insufficient refuge populations also may have contributed to other cases of Bt resistance [25].In general,larger populations of refuge insects will act to delay pest resistance by decreasing the proportion of homozygous resistant insects in a population,although the magnitude of this effect will depend on

the

Figure 2.Survival of western corn rootworm on Bt and non-Bt maize.Data are shown for A)Cry3Bb1maize and B)Cry34/35Ab1maize.In both cases,survival also is shown for a non-Bt near isogenic hybrid.Bar heights are means and error bars are the standard error of the mean.

doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0022629.g002

Figure 3.Correlation analysis for corrected survival of western corn rootworm.Correlations are shown for A)survival on Cry3Bb1maize and Cry34/35Ab1maize and B)survival on Cry3Bb1maize and number of years Cry3Bb1maize was planted in a field.Symbols in the graphs correspond to Table 1,which lists corrected survival for populations on Bt maize and the cultivation history of fields.For (A),no significant correlation was present between survival on Cry3Bb1maize and Cry34/35Ab1maize (r =0.068;df =6;P =0.87).For (B),a significant positive correlation was present between corrected survival on Cry3Bb1maize and the number of years Cry3Bb1maize had been grown in a field (r =0.832;df =7;P =0.005).doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0022629.g003

inheritance of resistance,with greater delays occurring for recessively inherited traits[24].

It is noteworthy that our findings are consistent with a greenhouse-selection experiment that found higher survival on Cry3Bb1maize by western corn rootworm after three generations of selection[16].In all of the problem fields we studied,Cry3Bb1 maize had been grown for at least three consecutive years (Table1),which corresponds to three generations of selection in this univoltine pest[7].Resistance to Cry3Bb1maize in the greenhouse-selected strain was incomplete,with the selected strain displaying lower fitness on Bt maize than non-Bt maize[16].In this study,populations from problem fields displayed lower survival on Cry3Bb1maize than non-Bt maize.This may have been due to resistance in problem fields being incomplete, populations from problem fields containing a mixture of resistant individuals from those fields and susceptible migrants for neighboring fields,or a combination of these two factors.

The landscape-level effects of the resistant populations identified in this study will depend on gene flow,fitness trade-offs that accompany resistance,and selection intensity[26,27,28,29]. Current trends in planting of Bt crops suggest that intense selection for resistance in the field will continue[1].Fitness costs could act to delay resistance,although the few data currently available suggest that costs of Bt resistance in western corn rootworm may be small[16,27].Western corn rootworm appears to have low rates of dispersal,typically traveling less than40m per day,although long-distance dispersal is possible[30,31].The tendency for short-distance dispersal may help to delay adaptation at a landscape level[29].Taken together these data suggest that resistance to Cry3Bb1maize in western corn rootworm should persist and intensify in localized areas,but at a landscape level, some populations may remain susceptible to Cry3Bb1maize.

It might be the case that the observed resistance by western corn rootworm to Cry3Bb1maize is a result of pre-adaptation rather than a response to selection.This is unlikely because of the high degree of genetic homogeneity observed among populations of this pest in the Midwest[32,33].This genetic similarity is thought to have resulted from the recent and rapid range expansion of the western corn rootworm from the Great Plains to the East Coast [7].Furthermore,there was a history of selection with Cry3Bb1 maize observed among problem fields(Table1)and a significant correlation between history of selection in the field and survival on Cry3Bb1maize in bioassays(Fig.3b),both of which support the proposition that resistance was the result of selection rather than pre-adaptation.

Recently,Bt maize was commercialized that produces both Cry3Bb1and Cry34/35Ab1[34].Pyramiding of multiple Bt toxins that target the same pest can delay the evolution of resistance to either toxin when most individuals that are resistant to one toxin are killed by the other toxin[35].In populations where western corn rootworm populations have begun adapting to Cry3Bb1,the benefit of pyramiding two Bt toxins may be diminished[36].However,the lack of cross resistance between these toxins(Fig.3a)suggests that pyramiding Cry3Bb1with Cry34/35Ab1may still act to delay resistance in problem fields at least as long as,if not longer than,the cultivation of maize producing only a single toxin.

Although no cases of field-evolved resistance were reported during the first decade of commercialization for Bt crops,several recent cases have been reported[12,25,37,38,39,40].Typically, there is a lag between the introduction of an insecticide and the first occurrence of resistance,which is then followed by a steady increase in the cumulative number of occurrences[41];a trend that would clearly be undesirable for Bt crops.Stern et al.[42] outlined the foundation of integrated pest management by advocating the application of multiple methods to control pest populations,thus delaying or avoiding problems that include,but are not limited to,pest resistance[43].To date,the widespread planting of Bt crops has resulted in pest resistance for only a small subset of all pest populations managed by this technology[18]. However,these recent cases suggest a need to develop more integrated management solutions for pests targeted by Bt crops [44,45].A common pattern observed among problem fields in this study was the consecutive planting of the same type of Bt maize over several seasons(Table1).Even with resistance management plans in place,sole reliance on Bt crops for management of agriculture pests will likely hasten the evolution of resistance in some cases,thereby diminishing the benefits that these crops provide.

Acknowledgments

We thank Bruce Tabashnik and Fred Gould for their comments on an earlier draft of this manuscript.

Author Contributions

Conceived and designed the experiments:AJG.Performed the exper-iments:JLP-M RSK MWD.Analyzed the data:AJG JLP-M.Wrote the paper:AJG JLP-M RSK.

References

1.James C(2010)Global Status of Commercialized Biotech/GM Crops:2010.

ISAAA Brief No.42.Ithaca,New York:ISAAA.

2.Carrie`re Y,Ellers-Kirk C,Sisterson MS,Antilla L,Whitlow M,et al.(2003)

Long-term regional suppression of pink bollworm by Bacillus thuringiensis cotton.

Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A100:1519–1523.

3.Cattaneo MG,Yafuso C,Schmidt C,Huang C-y,Rahman M,et al.(2006)

Farm-scale evaluation of the impacts of transgenic cotton on biodiversity, pesticide use,and yield.Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A103:7571–7576.

4.Huang J,Ruifa H,Rozelle S,Pray C(2005)Insect-resistant GM rice in farmers’

fields:assessing productivity and health effects in China.Science308:688–690.

5.Wu K-M,Lu Y-H,Feng H-Q,Jiang Y-Y,Zhao J-Z(2008)Suppression of cotton

bollworm in multiple crops in China in areas with Bt toxin-containing cotton.

Science321:1676–1678.

6.Hutchison W,Burkness E,Mitchell P,Moon R,Leslie T,et al.(2010)Areawide

suppression of European corn borer with Bt maize reaps savings to non-Bt maize growers.Science330:222–225.

7.Gray ME,Sappington TW,Miller NJ,Moeser J,Bohn MO(2009)Adaptation

and invasiveness of western corn rootworm:intensifying research on a worsening pest.Annu Rev Entomol54:303–321.

8.James C(2009)Global Status of Commercialized Biotech/GM Crops:2009.

ISAAA Brief No.41.Ithaca,New York:ISAAA.

9.Environmental Protection Agency(2003)Biopesticides registration action

document:event MON863Bacillus thuringiensis Cry3Bb1Corn.Available: https://www.sodocs.net/doc/a54018399.html,/pesticides/biopesticides/ingredients/tech_docs/cry3bb1/ 1_%20cry3bb1_exec_summ.pdf.

10.Gould F(1998)Sustainability of transgenic insecticidal cultivars:integrating pest

genetics and ecology.Annu Rev Entomol43:701–726.

11.Tabashnik BE,Gould F,Carrie`re Y(2004)Delaying evolution of insect

resistance to transgenic crops by decreasing dominance and heritability.J Evol Biol17:904–912.

12.Tabashnik BE,Gassmann AJ,Crowder DW,Carrie`re Y(2008)Insect resistance

to Bt crops:evidence versus theory.Nat Biotechnol26:199–202.

13.Meinke LJ,Siegfried BD,Wright RJ,Chandler LD(1998)Adult susceptibility of

Nebraska western corn rootworm(Coleoptera:Chrysomelidae)populations to selected insecticides.J Econ Entomol91:594–600.

14.Parimi S,Meinke LJ,French WB,Chandler LD,Siegfried BD(2006)Stability

and persistence of aldrin and methyl-parathion resistance in western corn rootworm populations(Coleoptera:Chrysomelidae).J Econ Entomol25: 269–274.

15.Levine E,Spencer JL,Isard SA,Onstad DW,Gray ME(2002)Adaptation of the

western corn rootworm to crop rotation:evolution of a new strain in response to

a management practice.Am Entomol48:94–107.

16.Meihls LN,Higdon ML,Siegfried BD,Miller NJ,Sappington TW,et al.(2008)

Increased survival of western corn rootworm on transgenic corn within three generations of on-plant greenhouse selection.Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A105: 19177–19182.

17.Jaffe G(2009)Complancency on the Farm:Significant Noncompliance with

EPA’s Refuge Requirements Threatens the Future Effectiveness of Genetically Engineered Pest-protected Corn.Washington,DC:Center for Science in the Public Interest.

18.Carrie`re Y,Crowder DW,Tabashnik BE(2010)Evolutionary ecology of insect

adaptation to Bt crops.Evol Appl3:561–573.

19.Nowatzki TM,Lefko SA,Binning RR,Thompson SD,Spencer TA,et al.(2008)

Validation of a novel resistance monitoring technique for corn rootworm (Coleoptera:Chrysomelidae)and event DAS-59122-7maize.J Appl Entomol 132:177–188.

20.Sokal RR,Rohlf FJ(1995)Biometry.New York:W.H.Freeman and Company.

21.Abbott WS(1925)A method of computing the effectiveness of an insecticide.

J Econ Entomol18:265–267.

22.Oleson JD,Park Y-L,Nowatzki TM,Tollefson JJ(2005)Node-injury scale to

evaluate root injury by corn rootworms(Coleoptera:Chrysomelidae).J Econ Entomol98:1–8.

23.Environmental Protection Agency(2010)Biopesticides Registration Action

Document.Available:https://www.sodocs.net/doc/a54018399.html,/oppbppd1/biopesticides/pips/ cry3bb1-brad.pdf.

24.Roush RT(1997)Bt-transgenic crops:just another pretty insecticide or a chance

for a new start in resistance management?Pestic Sci51:328–334.

25.van Rensburg JBJ(2007)First report of field resistance by stem borer,Busseola

fusca(Fuller)to Bt-transgenic maize.S Afr J Plant Soil24:147–151.

26.Sisterson MS,Carrie`re Y,Dennehy TJ,Tabashnik BE(2005)Evolution of

resistance to transgenic Bt crops:interactions between movement and field distribution.J Econ Entomol98:1751–1762.

27.Gassmann AJ,Carrie`re Y,Tabashnik BE(2009)Fitness costs of insect resistance

to Bacillus thuringiensis.Annu Rev Entomol54:147–163.

28.Jaffe K,Issa S,Daniels E,Haile D(1997)Dynamics of the emergence of genetic

resistance to biocides among asexual and sexual organisms.J Theor Biol188: 289–299.

29.Caprio MA(1992)Gene flow accelerates local adaptation among finite

populations:simulating the evolution of insecticide resistance.J Econ Entomol 85:611–620.

30.Spencer JL,Mabry TR,Vaughn TT(2003)Use of transgenic plants to measure

insect herbivore movement.J Econ Entomol96:1738–1749.

31.Spencer JL,Hibbard BE,Moeser J,Onstad DW(2009)Behaviour and ecology

of the western corn rootworm(Diabrotica virgifera virgifera LeConte).Agric For Entomol11:9–27.32.Coates BS,Sumerford DV,Miller NJ,Kim KS,Sappington TW,et al.(2009)

Comparative performance of singel nucleotide polymorphism and microsatellite markers for population genetic analysis.J Hered100:556–564.

33.Kim KS,Sappington TW(2005)Genetic structuring of western corn rootworm

(Coleoptera:Chrysomelidae)populations in the United States based on microsatellites loci analysis.Environ Entomol34:494–503.

34.Environmental Protection Agency(2009)Pesticide Fact Sheet.Available:http://

https://www.sodocs.net/doc/a54018399.html,/oppbppd1/biopesticides/pips/smartstax-factsheet.pdf.

35.Roush RT(1998)Two-toxin strategies for management of insecticidal transgenic

crops:can pyramiding succeed where pesticide mixtures have not?Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci353:1777–1786.

36.Onstad DW,Meinke LJ(2010)Modeling evolution of Diabrotica virgifera virgifera

(Coleoptera:Chrysomelidae)to transgenic corn with two insecticidal traits.

J Econ Entomol103:849–860.

37.Storer NP,Babcock JM,Schlenz M,Meade T,Thompson GD,et al.(2010)

Discovery and characterization of field resistance to Bt maize:Spodoptera frugiperda (Lepidoptera:Noctuidae)in Puerto Rico.J Econ Entomol103:1031–1038. 38.Downes S,Parker T,Mahon R(2010)Incipient resistance of Helicoverpa punctigera

to the Cry2Ab Bt toxin in bollgard II cotton.PLoS ONE5:e12567.

39.Bagla P(2010)Hardy cotton-munching pests are latest blow to GM crops.

Science327:1439.

40.Dhurua S,Gujar GT(2011)Field-evolved resistance to Bt toxin Cry1Ac in the

pink bollworm,Pectinophora gossypiella(Saunders)(Lepidoptera:Gelechiidae)from India.Pest Manag Sci67:doi:10.1002/ps.2127.

41.Metcalf RL(1986)The ecology of insecticides and the chemical control of

insects.In:Kogan M,ed.Ecological Theory and Integrated Pest Management Practices.New York:Wiley.pp251–297.

42.Stern VM,Smith RF,van den Bosch R,Hagen KS(1959)The integrated

control concept.Hilgardia29:81–101.

43.Pedigo LP,Rice ME(2009)Entomology and Pest Management.Upper Saddle

River:Pearson Education,Inc.

44.Tabashnik BE,Sisterson MS,Ellsworth PC,Dennehy TJ,Antilla L,et al.(2010)

Suppressing resistance to Bt cotton with sterile insect releases.Nat Biotechnol28: 1304–1307.

45.Baum JA,Bogaert T,Clinton W,Heck GR,Feldmann P,et al.(2007)Control of

coleopteran insect pests through RNA interference.Nat Biotechnol25:1322-1326.

46.Walters FS,Stacy CM,Lee MK,Palekar N,Chen JS(2008)An engineered

chymotrypsin/cathepsin G site domian I renders Bacillus thuringiensis Cry3A active against western corn rootworm larvae.Appl Environ Microbiol74: 367–374.

Westernblot实验步骤及注意事项1(精)

Westernblot实验步骤及注意事项 Westernblot 实验步骤 1. 组织块称重 2. 利用液氮、研钵粉碎组织块 3. 加入RIPA缓冲液(每克组织3 ml RIPA),PMSF(每克组织30μl,10 mg/ml PMSF),利用Polytron进一步匀浆(15,000转/分*1分钟)维持4℃ 4. 加入PMSF(每克组织30μl,10 mg/ml PMSF),冰上孵育30分钟 5. 移入离心管4℃约20,000 g(约15,000转)15分钟 6. 上清液为细胞裂解液可分装-20℃保存 7. 进行Bradford比色法测定蛋白质浓度 8. 取相同质量的细胞裂解液(体积*蛋白质浓度),并加等体积的2×电泳加样缓冲液 9. 沸水浴中3分钟 10. 上样 11. 电泳(浓缩胶20mA,分离胶35mA) 12. 电转膜仪转膜(100mA 40分钟) 13. 膜用丽春红染色,胶用考马斯亮蓝染色 14. Westernblot 试剂盒显色 15. 分析比较记录 western blot的实验步骤及注意事项的资料 1. 把聚丙烯酰胺凝胶中的蛋白质电泳转移到硝酸纤维膜上。 1)转移缓冲液洗涤凝胶和硝酸纤维素膜,将硝酸纤维素膜铺在凝胶上,用5ml移液管在凝胶上来回滚动去除所有的气泡。 2)在凝胶/滤膜外再包一张3mm滤纸(预先用转移缓冲液浸湿),将凝胶夹在中间,保持湿润和没有气泡。 3)将此滤纸/凝胶/薄膜滤纸按照厂家建议方法放入电泳装置中,凝胶面向阴极。

4)将上述装置放入缓冲液槽中,并灌满转移缓冲液以淹没凝胶。 5)按照厂家所示接通电源开始电泳转移。 6)转移结束后,取出薄膜和凝胶,弃去凝胶。 2. 将薄膜漂在氨基黑中快速染色,直至分子量标准显现时取出,记录下标准位置。 3. 用100ml水洗涤纤维素膜,必要时可用脱色缓冲液。 4. 膜置印迹缓冲液中于37℃保温1小时。 5. 室温下,用PBS-Tween缓冲液洗涤薄膜。 6. 用封口机将薄膜封入塑料袋中,尽可能不留空气。 7.袋的一角剪一缓冲液的小口,用透析袋夹紧。 8.混合:NGS(100微升),印迹缓冲液中的抗体(10毫升),加在装薄膜的袋中,于室温下摇动2小时(或4℃过夜) 9.用总体积300ml PBS-Tween缓冲液,分4次在一浅盘中洗涤薄膜,每次75ml。 10.将连接生物素的羊抗兔IgG(40微升溶于10毫升印迹缓冲液/100微升NGS)加在袋内,于室温下摇动1小时。 11.按步骤9洗涤。 12.加入抗生素蛋白-HRP(40微升溶于10毫升印迹缓冲液/100微升NGS),于室温下摇动。注意事项: western blot中转移在膜上的蛋白处于变性状态,空间结构改变,因此那些识别空间表位的抗体不能用于western blot检测。这种情况可以将表达目的蛋白的细胞或细胞裂解液中的所有蛋白先生物素化,再用酶标记亲和素进行western blot。实验中取胶和膜需带手套。 Western实验步骤 Western,也称Western blot、Western blotting、Western印迹,是用抗体检测蛋白的重要方法之一。Western可以参 考如下步骤进行操作。 1. 收集蛋白样品(Protein sample preparation) O 可以使用适当的裂解液,例如碧云天生产的Western及IP细胞裂解液,裂解贴壁细胞、悬浮细胞或组织样品。对于某些特定的亚 细胞组份蛋白,例如细胞核蛋白、细胞浆蛋白、线粒体蛋白等,可以参考相关文献提取这些亚细胞组份蛋白,也可以使用试剂盒 进行抽提,例如碧云天生产的细胞核蛋白与细胞浆蛋白抽提试剂盒。 O 收集完蛋白样品后,为确保每个蛋白样品的上样量一致,需要测定每个蛋白样品的蛋白浓度。根据所使用的裂解液的不同,需要 采用适当的蛋白浓度测定方法。因为不同的蛋白浓度测定方法对于一些去垢剂和还原剂等的兼容性差别很大。如果使用碧云天生

实验室常用溶液及试剂配制(重新排版)

实验室常用溶液及试剂配制 一、实验室常用溶液、试剂的配制-------------------------------------------------------1 表一普通酸碱溶液的配制 表二常用酸碱指示剂配制 表三混合酸碱指示剂配制 表四容量分析基准物质的干燥 表五缓冲溶液的配制 1、氯化钾-盐酸缓冲溶液 2、邻苯二甲酸氢钾-氢氧化钾缓冲溶液 3、邻苯二甲酸氢钾-氢氧化钾缓冲溶液 4、乙酸-乙酸钠缓冲溶液 5、磷酸二氢钾-氢氧化钠缓冲溶液 6、硼砂-氢氧化钠缓冲溶液 7、氨水-氯化铵缓冲溶液 8、常用缓冲溶液的配制 二、实验室常用标准溶液的配制及其标定-----------------------------------------------4 1、硝酸银(C AgNO3=0.1mol/L)标准溶液的配制 2、碘(C I2=0.1mol/L)标准溶液的配制 3、硫代硫酸钠(C Na2S2O3=0.1mol/L)标准溶液的配制 4、高氯酸(C HClO4=0.1mol/L)标准溶液的配制 5、盐酸(C HCl=0.1mol/L)标准溶液的配制 6、乙二胺四乙酸二钠(C EDTA =0.1mol/L)标准溶液的配制 7、高锰酸钾(C K2MnO4=0.1mol/L)标准溶液的配制 8、氢氧化钠(C NaOH=1mol/L)标准溶液的配制 三、常见物质的实验室试验方法 ----------------------------------------------------------6 1、柠檬酸(C6H8O7·H2O) 2、钙含量测定(磷酸氢钙CaHPO4、磷酸二氢钙Ca(H2PO4)2·H2O、钙粉等) 3、氟(Fˉ)含量的测定 4、磷(P)的测定 5、硫酸铜(CuSO4·5H2O) 6、硫酸锌(ZnSO4·H2O) 7、硫酸亚铁(FeSO4·H2O) 8、砷 9、硫酸镁(MgSO4) 四、维生素检测--------------------------------------------------------------------------------8 1、甜菜碱盐酸盐 2、氯化胆碱

westernblot详细图解

Western免疫印迹(Western Blot)是将蛋白质转移到膜上,然后利用抗体进行检测的方法。对已知表达蛋白,可用相应抗体作为一抗进行检测,对新基因的表达产物,可通过融合部分的抗体检测。 与Southern或Northern杂交方法类似,但Western Blot采用的是聚丙烯酰胺凝胶电泳,被检测物是蛋白质,“探针”是抗体,“显色”用标记的二抗。 经过PAGE分离的蛋白质样品,转移到固相载体(例如硝酸纤维素薄膜)上,固相载体以非共价键形式吸附蛋白质,且能保持电泳分离的多肽类型及其生物学活性不变。以固相载体上的蛋白质或多肽作为抗原,与对应的抗体起免疫反应,再与酶或同位素标记的第二抗体起反应,经过底物显色或放射自显影以

检测电泳分离的特异性目的基因表 达的蛋白成分。该技术也广泛应用 于检测蛋白水平的表达。 实验材料蛋白质样品 试剂、试剂盒丙烯酰胺SDS Tris-HCl β-巯基乙醇 ddH2O 甘氨酸Tris 甲醇PBS NaCl KCl Na2HPO4 KH2PO4 ddH2O 考马斯亮兰乙酸脱脂奶粉硫酸镍胺H2O2 DAB试剂盒 仪器、耗材 电泳仪电泳槽离心机离心管硝酸纤维素 膜匀浆器剪刀移液枪刮棒 实验步骤一、试剂准备 1. SDS-PAGE试剂:见聚丙烯酰胺凝胶电泳实验。 2. 匀浆缓冲液:1.0 M Tris-HCl(pH 6.8) 1.0 ml;10%SDS 6.0 ml;β-巯基乙醇0.2 ml;ddH2O 2.8 ml。 3. 转膜缓冲液:甘氨酸2.9 g;Tris 5.8 g;SDS 0.37 g;甲醇200 ml;加ddH2O定容至1000 ml。

常用实验试剂配制

1DEPC水(1‰) 1000ml 水 1ml DEPC 根据需要确定要配的体积,泡实验器具的DEPC水静止4小时后备用,泡24小时。配液体的DEPC水37℃过夜,送至高压,然后配相关溶液。 20.1M tris(ph 7.5) 12.114g tris 1000ml DEPC水 用HCL调ph至7.5,高压备用。 3 4%PFA的配制(ph 7.0)40g PFA 1000ml 0.1m tris(DEPC水配制高压) 将溶液持续加热至60℃左右,搅拌之至完全溶解,注意温度不要超过65℃,否则PFA降解失效。 30.2% 甘油/0.1M tris 20ml 甘油 980ml 0.1Mtris 4 20XSSC Nacl 175.3g (ph 7.0)柠檬酸钠88.2g DEPC水1000ml 分别稀释至2XSSC和0.2XSSC备用 5 HEPES 溶液HEPES 23.8g (ph6.8-8.0)DEPC H2O 100ml 6 50X Denhaldt′s 液 聚蔗糖(Ficoll 400)0.2g 聚乙烯吡咯烷酮(polyvinypyrrolidone) 0.2g 牛血清蛋白(BSA)0.2g DEPC 水20ml 7 预杂交buffer Deinoized formanmid 5ml 20X SSC 1.5ml 1M HEPES 0.5ml 50X Denhanldt′s液1ml 龟精DNA 0.6ml(4ug/ul) DEPC水 1.4ml 龟精DNA 要先95℃10-15min加热变性,随即冰浴。杂交buffer分装后-20℃保存。 8Washing buffer (ph7.5) maleic acid 5.8g NACL 4.4g Tween(吐温) 1.5ml 定容至500ml溶质浓度最后分别为0.1M maleic acid 0.15M nacl 0.3% Tween 9Maleic acid buffer (ph7.5) Maleic acid 5.8g Nacl 4.4g 定容至500ml 溶质的浓度最后分别为0.1M maleic acid 0.15M nacl 10Detection buffer

Western Blot常见问题及处理总结

免疫细胞研究western blot Western Blot常见问题及处理总结 阿木 1、western blot 的优点 答:灵敏,可达ng级,用Ecl显色法理论上可达pg 级。方便,特异性高。 2、为什么我的细胞提取液中没有目标蛋 白? 答:原因有很多: a) 你的细胞中不表达这种蛋白质,换一种细胞;b) 你的细胞中的蛋白质被降解掉了,你必需加入PMSF,抑制蛋白酶活性;c) 你的抗体不能识别目标蛋白,多看看说明,看是否有问题。 3、我的细胞提取液有的有沉淀,有的很 清亮,为什么呢?

答:a) 有沉淀可能因为你的蛋白没有变性完全,可以适当提高SDS 浓度,同时将样品煮沸时间延长,b) 也不排除你的抗原浓度过高,这时再加入适量上样缓冲 液即可。 4、我做的蛋白质分子量很小(10KD), 请问怎么做WB? 答:可以选择0.2μml的膜,同时缩短转移时间。也可以将两张膜叠在一起,再转移。 其他按步骤即可。 5、我的目的带很弱,怎么加强? 答:可以加大抗原上样量。这是最主要的。 同时也可以将一抗稀释比例降低。 6、胶片背景很脏,有什么解决方法?答:减少抗原上样量,降低一抗浓度,改

变一抗孵育时间,提高牛奶浓度。 7、目标带是空白,周围有背景,是为什 么? 答:你的一抗浓度较高,二抗上HRP 催化活力太强,同时你的显色底物处于一个临界点,反应时间不长,将周围底物催化完,形成了空白即“反亮现象”。将一抗和二抗浓度降低,或更换新底物。 8、我的胶片是一片空白,是怎么回事? 答:如果能够排除下面的几个问题那么问题多半出现在一抗和抗原制备上。 a) 二抗的HRP 活性太强,将底物消耗光;b) ECM底物中H2O2,不稳定,失活;c) ECL底物没覆盖到相应位置;d) 二 抗失活。

western blot操作注意事项

一.配胶 1.注意一定要将玻璃板洗净,最后用ddH2O冲洗,将与胶接触的一面向下倾斜置于干净的纸巾晾干。 2.分离胶及浓缩胶均可事先配好(除AP及TEMED外),过滤后作为储存液避光存放于4℃,可至少存放1个月,临用前取出室温平衡(否则凝胶过程产生的热量会使低温时溶解于储存液中的气体析出而导致气泡,有条件者可真空抽吸3分钟),加入10%AP(0.7~0.8:100, 分离胶浓度越高AP浓度越低,15%的分离胶可用到0.5:100)及TEMED(分离胶用0.4:1000, 15%的可用到0.3:1000,浓缩胶用0.8:1000)即可 3.封胶:灌入2/3的分离胶后应立即封胶,胶浓度<10%时可用0.1%的SDS封,浓度>10%时用水饱和的异丁醇或异戊醇,也可以用0.1%的SDS。封胶后切记,勿动。待胶凝后将封胶液倒掉,如用醇封胶需用大量清水及ddH2O冲洗干净,然后加少量0.1%的SDS,目的是通过降低张力清除残留水滴。 4.灌好浓缩胶后1h拔除梳子,注意在拔除梳子时宜边加水边拔,以免有气泡进入梳孔使梳孔变形。拨出梳子后用ddH2O冲洗胶孔两遍以去除残胶,随后用0.1%的SDS封胶。若上样孔有变形,可用适当粗细的针头拨正;若变形严重,可在去除残胶后用较薄的梳子再次插入梳孔后加水拔出。30min后即可上样,长时间有利于胶结构的形成,因为肉眼观的胶凝时其内部分子的排列尚未完成。 二.样品处理 1.培养的细胞(定性): ⑴去培养液后用温的PBS冲洗2~3遍(冷的PBS有可能使细胞脱落)。 ⑵对于6孔板来说每孔加200~300μl,60~80℃的1×loading buffer。 ⑶100℃,1min。 ⑷用细胞刮刮下细胞后在EP管中煮沸10min,期间vortex 2~3次。 ⑸用干净的针尖挑丝,如有团块则将团块弃掉,如果没有团块但有拉丝现象,则可以将EP 管置于0℃后在14000~16000g离心2min,再次挑丝。若无团块也无丝状物但溶液有些粘稠,可通过使用1ml注射器反复抽吸来降低溶液粘滞度,便于上样。 ⑹待样品恢复到室温后上样。 2.培养的细胞(定量): ⑴去培养液后用温的PBS冲洗2~3遍(冷的PBS有可能使细胞脱落)。 ⑵加入适量的冰预冷的裂解液后置于冰上10~20min。 ⑶用细胞刮刮下细胞,收集在EP管后超声(100~200w)3s,2次。 ⑷12000g离心,4℃,2min。 ⑸取少量上清进行定量。 ⑹将所有蛋白样品调至等浓度,充分混合沉淀后加loading buffer后直接上样最好,剩余溶液(溶于1×loading buffer)可以低温储存,-70℃一个月,-20℃一周,4℃1~2天,每次上样前98℃,3min。 3.组织: ⑴匀浆对于心肝脾肾等组织可每50~100mg加1ml裂解液,肺100~200mg加1ml裂解液。可手动或电动匀浆。注意尽量保持低温,快速匀浆。 ⑵12000g离心,4℃,2min。 ⑶取少量上清进行定量。 ⑷将所有蛋白样品调至等浓度,充分混合沉淀加loading buffer后直接上样最好,剩余溶液

western blot实验经验总结

western blot实验经验总结 1.抗体的选择 对于国内的大多数实验室来讲,做western blot实验选择抗体是个头疼的问题。原因很简单,买进口抗体捉襟见肘,买国产抗体得需要大无畏的勇气,对于我所在的兰州地区的实验者而言,感触尤深。在这五年的western blot实验历程里,我先后用过进口抗体,进口抗体国内分装包装,国产抗体,质量良莠不齐。 进口抗体一般不会出现闪失:abcam品种全,质量过硬,但价高(3400元/100微升),而且说是100微升,但至多能吸出来90微升;Sigma的价最贵;比较有性价比的是CST的抗体,现在好像是2200元/100微升,我前后用过二十几种, 1:1000的稀释比下,还没有失过手,100微升通常能完成所有的免疫组化和western blot 实验,还有一个优点是通常量比100微升多出来10微升,唯一的不足是CST的品种实在不多。Santa的多克隆抗体质量可以,但是选用Santa的单抗还是有风险,估计这也是业界共识了吧。 进口抗体国内分装包装我也用过不少,呵呵,毕竟是穷人(420元/100微升),大概好抗体的比例约为50%,如果能做出来,也存在一个问题,就是抗体大多只能用一次。我曾经把Santa的原装抗体和分装抗体做过比对(抗体品种,货号等完全一致),在都能做出来的前提下,原装抗体能重复使用的次数要多出许多。具体原因我已经揣测了好几年,不敢说出来,我一直在想是不是冬天西瓜切成牙和整个卖,也会有所不同。揣测归揣测,假如只为了发论文毕业走人,可以考虑选用进口分装的多克隆抗体。 国产抗体比较知名的就几家,但质量确实不敢恭维。western blot能做出来的确实不多,而且杂带多,背景不干净。我们周边的实验室大多买国产抗体做免疫组化,怎么说呢,应付硕士论文够了。 我也帮别人自制过抗体,再用抗原亲和纯化。效价非常不错,夸张的时候1:10000都能做出条带,唯一的麻烦是兔子太骚(骚臭),不知道这是不是“兔女郎”名号的来由。如果读书非常悠闲,老板又特别想拥有手工作坊的情况下,可以自己伺候折腾兔子来玩玩,刚开始的时候还是蛮有成就感的。只是单凭抗原表达和制备多抗,是不是可以写成论文毕业,估计因校而异了。 2.Western Blot设备 目前最好的垂直槽和转移槽还是Biorad(伯乐),尤其是MINI3好用,MINI4可以一次跑四块胶,但通常用不上,由此造成垂直缓冲液的浪费,而且MINI4用绿色塑料夹住玻璃板来组成内槽,容易漏液,塑料夹应该是有疲劳寿命的,估计日子一长,弹性就会改变,所以如果你们实验室刚买了MINI4,赶紧用,遭殃的肯定是某一级的师弟师妹们。 Biorad的一套系统得两万多,西部能玩得起伯乐的还真不多。好在咱中国人聪明,上海天能的外观和构造和伯乐的MINI3几乎一模一样,而且可以通用,不带电泳仪是5千多一套,挺好用的。唯一的不足是塑料寿命不如伯乐,胶架容易断裂。不过仔细算算,三套天能也就是一套伯乐的价格,值了。北京六一的垂直槽

蛋白质印迹法westernblot

蛋白质印迹法 蛋白质印迹法(免疫印迹试验)即Western Blot。它是分子生物学、生物化学和免疫遗传学中常用的一种实验方法。 其基本原理是通过特异性抗体对凝胶电泳处理过的细胞或生物组织样品进行着色。通过分析着色的位置和着色深度获得特定蛋白质在所分析的细胞或组织中表达情况的信息。 蛋白免疫印迹(Western Blot )是将电泳分离后的细胞或组织总蛋白质从凝胶转移到固相支持物NC膜或PVDF膜上,然后用特异性抗体检测某特定抗原的一种蛋白质检测技术,现已广泛应用于基因在蛋白水平的表达研究、抗体活性检测和疾病早期诊断等多个方面。 中文名蛋白质印迹法外文名Western Blot 蛋白免疫印迹Western Blot 类似方法1 Southern Blot 杂交方法 类似方法2 Northern Blot 杂交方法 使用材料聚丙烯酰氨凝胶电泳⑴

原理 与Southern Blot 或Northern Blot 杂交方法类似,但Western Blot法采用的是聚丙烯酰胺凝胶电泳,被检测物是蛋白质,“探针”是抗体,“显色”用标记的二抗。经过PAG(聚丙烯酰胺凝胶电泳)分离的蛋白质样品,转移到固相载体(例如硝酸纤维素薄膜)上,固相载体以非共价键形式吸附蛋白质,且能保持电泳分离的多肽类型及其生物学活性不变。以固相载体上的蛋白质或多肽作为抗原,与对应的抗体起免疫反应,再与酶或同位素标记的第二抗体起反应,经过底物显色或放射自显影以检测电泳分离的特异性目的基因表达的蛋白成分。该技术也广泛应用于检测蛋白水平的表达。⑴ 分类 Western Blot 显色的方法主要有以下几种: i. 放射自显影 ii. 底物化学发光ECL iii. 底物荧光ECF iv. 底物DAB呈色

westernblot详细图解详细版.docx

Western免疫印迹(Western Blot) 是将蛋白质转移到膜上,然后利用 抗体进行检测的方法。对已知表达 蛋白,可用相应抗体作为一抗进行 检测,对新基因的表达产物,可通 过融合部分的抗体检测。 与Southern或Northern杂交方法 类似,但Western Blot采用的是聚 丙烯酰胺凝胶电泳,被检测物是蛋 白质,“探针”是抗体,“显色”用标记 的二抗。 经过PAGE分离的蛋白质样品,转 移到固相载体(例如硝酸纤维素薄 膜)上,固相载体以非共价键形式 吸附蛋白质,且能保持电泳分离的 多肽类型及其生物学活性不变。以 固相载体上的蛋白质或多肽作为抗 原,与对应的抗体起免疫反应,再 与酶或同位素标记的第二抗体起反 应,经过底物显色或放射自显影以 检测电泳分离的特异性目的基因表 达的蛋白成分。该技术也广泛应用 于检测蛋白水平的表达。 实验材料蛋白质样品 试剂、试剂盒丙烯酰胺SDS Tris-HCl β-巯基乙醇 ddH2O 甘氨酸Tris 甲醇PBS NaCl KCl Na2HPO4 KH2PO4 ddH2O 考马斯亮兰乙酸脱脂奶粉硫酸镍胺H2O2 DAB试剂盒 仪器、耗材电泳仪电泳槽离心机离心管硝酸纤维素膜匀浆器剪刀移液枪刮棒 实验步骤一、试剂准备 1. SDS-PAGE试剂:见聚丙烯酰胺凝胶电泳实验。 2. 匀浆缓冲液:1.0 M Tris-HCl(pH 6.8) 1.0 ml;10%SDS 6.0 ml;β-巯基乙醇0.2 ml;ddH2O 2.8 ml。 3. 转膜缓冲液:甘氨酸2.9 g;Tris 5.8 g;

SDS 0.37 g;甲醇200 ml;加ddH2O定容至1000 ml。 4. 0.01 M PBS(pH7.4):NaCl 8.0 g;KCl 0.2 g;Na2HPO4 1.44 g;KH2PO4 0.24 g;加ddH2O至1000 ml。 5. 膜染色液:考马斯亮兰0.2 g;甲醇80 ml;乙酸2 ml;ddH2O118 ml。包被液(5%脱脂奶粉,现配):脱脂奶粉1.0 g 溶于20 ml的0.01 M PBS中。 6. 显色液:DAB 6.0 mg;0.01 M PBS 10.0 ml;硫酸镍胺0.1 ml;H2021.0 μl。 二、蛋白样品制备 1. 单层贴壁细胞总蛋白的提取 (1)倒掉培养液,并将瓶倒扣在吸水纸上使吸水纸吸干培养液(或将瓶直立放置一会儿使残余培养液流到瓶底然后再用移液器将其吸走)。 (2)每瓶细胞加3 ml 4℃预冷的PBS (0.01M pH7.2~7.3)。平放轻轻摇动1 min 洗涤细胞,然后弃去洗液。重复以上操作两次,共洗细胞三次以洗去培养液。将PBS弃净后把培养瓶置于冰上。 (3)按1ml裂解液加10 μl PMSF(100 mM),摇匀置于冰上。(PMSF要摇匀至无结晶时才可与裂解液混合。) (4)每瓶细胞加400 μl含PMSF的裂解液,于冰上裂解30 min,为使细胞充分裂解培养瓶要经常来回摇动。 (5)裂解完后,用干净的刮棒将细胞刮于培养瓶的一侧(动作要快),然后用枪将细胞碎片和裂解液移至1.5 ml离心管中。(整个操作尽量在冰上进行。) (6)于4℃下12000 rpm离心5 min。(提

实验室常用生化试剂配方

实验室常用生化试剂配方 1.常用抗生素配制以及使用说明(参考链霉菌室操作手册2019版) 抗生素 英文名称及缩写 抗性基因 贮藏液浓度(mg/ml) 100 25(无水乙醇配) 50 25 50 50 25(DMSO配) 100 50 35 25(0.15M NaOH配) 50(DMSO配) 50 50 MM 使用终浓度(μg/ml)链霉菌 2CM YEME 大肠杆菌 LA或LB 氨苄青霉素氯霉素潮霉素卡那霉素壮观霉素链霉素硫链丝菌素红霉素阿泊拉霉素紫霉素萘锭酮酸 TMP Ampicillin, Amp bla Chloramphenicol, Cml Hygromycin, Hyg Kanamycin, Km Spectinomycin, Spc Streptomycin, Str Thiostrepton, Thio Erythomycin, Ery Apramycin, Am Viomycin,Vio Nalidixic acid Trimethoprim cat hyg aac/aph aadA str tsr ermE aac(3)IV vph -* 10 10 2 5 10 5 100 10 -- 25 25 20 25 10 - 50 ------ 2.5 - 5 50-100 25 - 25 50 25 25 20 10-30

注意事项: (1) –表示无记录或不能使用,贮存液除特别说明外均用无菌水配制,配制过程请 确保抗生素粉末充分溶解混匀后再分装; (2)Km 和Am有交叉抗性,同时具有这两种抗性基因时应适当提高抗生素的量,并 设置阴性对照; (3)Hyg、Vio易见光分解,配制好后应用锡箔纸包好,使用过程中建议避光操作。有些抗生素需要在低盐的环境(如DNA培养基)下筛选效率较高,如Hyg, Km, Vio (4)用无菌水配制的抗生素需在超净工作台内用0.22 μm一次性过滤器过滤除菌并 分装;氯霉素、TMP、硫链丝菌素可以在超净工作台外配制分装,无需过滤除菌,但需确 保配制贮存液所用溶剂(无水乙醇、DMSO)未遭受污染,建议配制氯霉素时使用新的无水 乙醇,不要使用抽提质粒或总DNA时用的无水乙醇,以防止污染;DMSO,即二甲亚砜,易 挥发,有剧毒; (5)长期不用的抗生素请置于-20℃保存,抗生素粉末按照使用说明一般置于4℃保存,经常使用时可以暂置于4℃保存; (6)抗生素的实际使用浓度请结合实验经验进行适当调整; (7)配制抗生素时应尽量一次性称取抗生素粉末,配制过程中建议穿工作服,戴一次 性橡胶手套及口罩,及时清理称量配制抗生素时使用的台面及器具,以避免抗生素及溶剂 对自身的损伤及对工作环境的污染。 注意事项: (1)表中所列酶均可以用无菌水配制,也可以用相应的缓冲液配制,缓冲液配制方法 参考《分子克隆实验指南(第3版)》: 蛋白酶 K缓冲液:50 mM Tris(pH 8.0),1.5 mM 乙酸钙; RNase A缓冲液:TE (pH 7.6):10 mM Tris-HCl,1 mM EDTA;溶菌酶缓冲液:10 mM Tris-HCl(pH 8.0); (2) RNase A配制好后沸水浴处理5 min,取出贮存RNase A后首次使用时也需沸水 浴处理5 min后再使用; (3)制备原生质体时使用的溶菌酶配制时需过滤除菌,其他情况一般无需过滤除菌; (4)所有酶均应在-20℃保存,使用过程中避免反复冻融,配制过程中尽量避免外界 污染。 (1)IPTG用无菌水配制,0.22μm一次性滤膜过滤除菌,分装保存于-20℃;

最详细的WesternBlot过程步骤详解

最详细的W e s t e r n B l o t 过程步骤详解

最详细的W e s t e r n B l o t 过程步骤详解 Pleasure Group Office【T985AB-B866SYT-B182C-BS682T-STT18】

Western Blot详解(原理、分类、试剂、步骤及问题解答) Western免疫印迹(Western Blot)是将蛋白质转移到膜上,然后利用抗体进行检测。对已知表达蛋白,可用相应抗体作为一抗进行检测,对新基因的表达产物,可通过融合部分的抗体检测。 本文主要通过以下几个方面来详细地介绍一下Western Blot技术: 一、原理 二、分类 i.放射自显影 ii.底物化学发光ECL ECF iv.底物DAB呈色 三、主要试剂 四、主要步骤 五、实验常见的问题指南 1.参考书推荐 2.针对样品的常见问题 3.抗体 4.滤纸、胶和膜的问题 的相关疑问 6.染色的选择 7.参照的疑问

8.缓冲液配方的常见问题 9.条件的摸索 10.方法的介绍 11.结果分析 一、原理 与Southern或Northern杂交方法类似,但Western Blot采用的是聚丙烯酰胺凝胶电泳,被检测物是蛋白质,“探针”是抗体,“显色”用标记的二抗。经过PAGE分离的蛋白质样品,转移到固相载体(例如硝酸纤维素薄膜)上,固相载体以非共价键形式吸附蛋白质,且能保持电泳分离的多肽类型及其生物学活性不变。以固相载体上的蛋白质或多肽作为抗原,与对应的抗体起免疫反应,再与酶或同位素标记的第二抗体起反应,经过底物显色或放射自显影以检测电泳分离的特异性目的基因表达的蛋白成分。该技术也广泛应用于检测蛋白水平的表达。 二、分类 现常用的有底物化学发光ECL和底物DAB呈色,体同水平和实验条件的是用第一种方法,目前发表文章通常是用底物化学发光ECL。只要买现成的试剂盒就行,操作也比较简单,原理如下(二抗用HRP标记):反应底物为过氧化物+鲁米诺,如遇到HRP,即发光,可使胶片曝光,就可洗出条带。

WB实验问题

Western Blot问题指南 时间:2011-05-13 08:55 来源:网络作者:admin点击:3679次 根据问题的类型主要分成以下几类(以下资料权作参考,请勿盲目模仿!); 1.参考书 推荐A.对初学者看什么资料比较好?解答:《抗体技术实验指南》和Antibodies (a laboratory manual , 根据问题的类型主要分成以下几类(以下资料权作参考,请勿盲目模仿!); 1. 参考书推荐 A. 对初学者看什么资料比较好? 解答:《抗体技术实验指南》和Antibodies (a laboratory manual,wrote by Ed Harlow ,david lane )两本书不错。 2. 针对样品的常见问题 B. 做线粒体膜UCP蛋白的Western Blot (以下简写成Western Blot),提取线粒体后冻存(未加蛋白酶抑制剂),用的博士德的一抗,开始还有点痕迹,现在越来越差,上样量已加到120 口g,换了个santa cloz 的一抗仍不行。是什么原因?蛋白酶抑制剂单力口PMSF亍吗? 解答:怀疑是样品问题,可能是:1,样品不能反复冻融;2,样品未加蛋白酶抑制剂。同时,建议检查Western Blot过程,提高一抗浓度。对于加蛋白酶抑制剂来说,一般加PMSF就可以了,最好能多加几中种蛋白酶抑制剂。 C. 同一蛋白样品能同时进行两种因子的Western Blot检测吗? 解答:当然可以,有的甚至可以同时测几十种样品。 D. 如果目标蛋白是膜蛋白或是胞浆蛋白,操作需要注意什么? 解答:如果是膜蛋白和胞浆蛋白,所用的去垢剂就要温和得多,这时最好加上NaF去抑 制磷酸化酶的活性。 E我的样品的蛋白含量很低,每微升不到1微克,但是在转膜时经常会发现只有一部分 蛋白转到了膜上,就是在转膜后染胶发现有的孔所有的蛋白条带都在,只是颜色变淡了, 有什么办法可以解决? 解答:你可以加大上样量,没有问题,还有转移时你可以用减少电流延长时间,多加5—10%甲醇。 F. 想分离的蛋白是分子量260kd的,SDS-PAGE电泳的分离胶浓度多大合适?积层胶的 浓度又该用多少?这么大分子量的蛋白容易作Wester n Blot吗? 解答:260kd的蛋白不好做,分离胶用6%, Stacking Gel 3.5 %。 G. 如果上样量超载,要用什么方法来增加上样量?如果需要加大上样量使原来弱的条带能看清楚。 解答:可以浓缩样品,也可以根据你的目标分子量透析掉一部分小分子蛋白。一般地,超载30%是不会有问题的。如果已经超了不少了,而且小分子量的也要,可以考虑加大胶的厚度,可以试试1.5m m的comb。

实验室药品的取用和溶液的配制

实验室药品的取用和溶液的配制 1 固体试剂的取用规则 (1)要用干净的药勺取用。用过的药勺必须洗净和擦干后才能再使用,以免沾污试剂。 (2)取用试剂后立即盖紧瓶盖。 (3)称量固体试剂时,必须注意不要取多,取多的药品,不能倒回原瓶。 2 液体试剂的取用规则 (1)从滴瓶中取液体试剂时,要用滴瓶中的滴管,滴管绝不能伸入所用的容器中,以免接触器壁而沾污药品。从试剂瓶中取少量液体试剂时,则需要专用滴管。装有药品的滴管不得横置或滴管口向上斜放,以免液体滴入滴管的胶皮帽中。 (2)使用胶头滴管“四不能”:不能伸入和接触容器内壁,不能平放和倒拿,不能随意放置,未清洗的滴管不能吸取别的试剂。 (3)配制一定物质的量溶液时,溶解或稀释后溶液应冷却再移入容量瓶。 (4)配制一定物质的量浓度溶液,要引流时,玻璃棒的上面不能靠在容量瓶口,而下端则应靠在容量瓶刻度线下的内壁上(即下靠上不靠,下端靠线下)。 (5)容量瓶不能长期存放溶液,更不能作为反应容器,也不能互用。(一般用于配制标准溶液的容量瓶最好专用) 3 溶液的配制 (1)配制溶质质量分数一定的溶液 计算:算出所需溶质和水的质量。把水的质量换算成体积。如溶质是液体时,要算出液体的体积。 称量:用天平称取固体溶质的质量;用量筒量取所需液体、水的体积。 溶解:将固体或液体溶质倒入烧杯里,加入所需的水,用玻璃棒搅拌使溶质完全溶解。(2)配制一定物质的量浓度的溶液 计算:算出固体溶质的质量或液体溶质的体积。 称量:用托盘天平称取固体溶质质量,用量筒量取所需液体溶质的体积。 溶解:将固体或液体溶质倒入烧杯中,加入适量的蒸馏水用玻璃棒搅拌使之溶解,冷却到室温后,将溶液引流注入容量瓶里。 转移:用适量蒸馏水将烧杯及玻璃棒洗涤2-3 次,将洗涤液注入容量瓶,振荡,使溶液混合均匀。

Western Blot常见问题及处理总结

免疫细胞研究westernblot WesternBlot常见问题及处理总结 阿木 1、westernblot的优点 答:灵敏,可达ng级,用Ecl显色法理论上可达pg级。方便,特异性高。 2、为什么我的细胞提取液中没有目标蛋白? 答:原因有很多:a)你的细胞中不表达这种蛋白质,换一种细胞;b)你的细胞中的蛋白质被降解掉了,你必需加入PMSF,抑制蛋白酶活性;c)你的抗体不能识别目标蛋白,多看看说明,看是否有问题。 3、我的细胞提取液有的有沉淀,有的很清亮,为什么呢? 答:a)有沉淀可能因为你的蛋白没有变性完全,可以适当提高SDS浓度,同时将样品煮沸时间延长,b)也不排除你的抗原浓度过高,这时再加入适量上样缓冲液即可。 4、我做的蛋白质分子量很小(10KD),请问怎么做WB? 答:可以选择0.2μml的膜,同时缩短转移时间。也可以将两张膜叠在一起,再转移。其他按步骤即可。

5、我的目的带很弱,怎么加强? 答:可以加大抗原上样量。这是最主要的。同时也可以将一抗稀释比例降低。 6、胶片背景很脏,有什么解决方法? 答:减少抗原上样量,降低一抗浓度,改变一抗孵育时间,提高牛奶浓度。 7、目标带是空白,周围有背景,是为什么?答:你的一抗浓度较高,二抗上HRP催化活力太强,同时你的显色底物处于一个临界点,反应时间不长,将周围底物催化完,形成了空白即“反亮现象”。将一抗和二抗浓度降低,或更换新底物。 8、我的胶片是一片空白,是怎么回事? 答:如果能够排除下面的几个问题那么问题多半出现在一抗和抗原制备上。 a)二抗的HRP活性太强,将底物消耗光;b)ECM 底物中H2O2,不稳定,失活;c)ECL底物没覆盖到相应位置;d)二抗失活。 9、我在显影液中显影1分钟和5分钟后,底片漆黑一片,是什么原因呢? 答:a)可能是红灯造成的,胶片本来就被曝光了,可以在完全黑暗的情况下操作.看是否有改善.; b)显影时间过长。 10、DAB好还是ECM好?

分子实验常用试剂配制(精)

氨苄青霉素 ﹡组分浓度 100mg/ml 氨苄青霉素 ﹡配制量 50ml ﹡配制方法 1.称取 5g Ampicillin置于 50ml 塑料离心管中。 2.加入 40ml 灭菌水,充分混合溶解之后定容至 50ml 。 3. 0.22μm 滤膜过滤除菌,小份分装(1ml/管后,置于-20℃保存。卡那霉素 (可配 25mL ﹡组分浓度 50mg/ml卡那霉素 ﹡配制量 50ml ﹡配制方法 1.称取 2.5g 卡那霉素置于 50ml 塑料离心管中。 2.加入 40ml 灭菌水,充分混合溶解之后定容 50ml 。 3. 0.22μm 滤膜过滤除菌,小份分装(1ml/管后,置于-20℃保存。RNase A ﹡组分浓度 10mg/ml RNase A ﹡配制量 50ml ﹡配制方法 1.取 0.5g RNase A置于 50ml 塑料离心管中。

2.加入 40ml 灭菌水,充分混合溶解之后定容 50ml 。 3. 100℃煮沸 15min, 缓慢冷却至室温,小份分装(1ml/管后,置于-20℃保存。IPTG ﹡组分浓度 24mg/ml IPTG ﹡配制量 50ml ﹡配制方法 1.称取 1.2g IPTG置于 50ml 塑料离心管中。 2.加入 40ml 灭菌水,充分混合溶解之后定容 50ml 。 3.用0.22μm 滤膜过滤除菌,小份分装(1ml/管后,置于-20℃保存。 X-Gal ﹡组分浓度 20mg/ml X-Gal ﹡配制量 50ml ﹡配制方法 1.称取 1g X-Gal置于 50ml 塑料离心管中。 2.加入 40mlDMF (二甲基甲酰胺 ,充分混合溶解之后定容至 50ml 。 3.小份分装(1ml/管后,置于-20℃保存。 DTT ﹡组分浓度 1M DTT ﹡配制量 10ml

Western blot 实验技巧精要

Western blot 实验技巧精要 Western blot 方法在SCI 文章中出现的频率非常高,漂亮的WB 电泳图可以给文章增色不少。但是WB 实验的步骤琐碎,细节颇多,要想得到令人满意的结果还是需要花费很多时间和精力去摸索实验技巧的。 一、样品准备部分 我们不应该太过重视WB 电泳部分的操作技巧,样品准备才是整个WB 实验中最重要的一个环节(没有之一)。否则WB 电泳技术再高也无法得到好的结果。小编认为以下3 点值得大家重点关注: 1. 注意孵育、终止时间 如果想得到漂亮的梯度条带,无论是不同处理时间的样品,还是不同给药浓度的样品,在处理过程中都一定要严格按照设计的时间来孵育和终止,尤其是对于磷酸化蛋白,哪怕1 秒也不要提前或耽搁。 2. 抑制蛋白降解 这是样品制备中最需要注意的部分。抑制样品蛋白降解的方法主要有两种: (1) 使用蛋白酶抑制剂 罗氏公司(Roche)的蛋白酶抑制剂Cocktail 片剂,效果不错。再与PMSF 共同使用,可以很好地抑制蛋白降解。 (2) 全程低温操作 提前预冷PBS、裂解液甚至枪头等,从收集细胞开始一直到煮样的全过程都应该尽可能的保持在冰上操作。除了使用冰盒,大多数操作都是在4℃冷房中进行的,虽然有点麻烦和辛苦,但是效果非常好。 3. 裂解液用量 将收集好的细胞加入裂解液进行裂解在操作上是非常简单的,所以这一步的重要性很容易被大家忽视。裂解液的用量直接决定了细胞裂解程度以及裂解后的蛋白浓度。如果加入的裂解液不足,蛋白浓度太高,会造成与上样缓冲液反应不充分,电泳后会出现多条条带,条带形状也不好。做磷酸化蛋白检测时为了在每个胶孔中尽可能多上样,所以用体积较少的裂解液制备了浓度很高的蛋白,结果就得不偿失了(见下图)。

western-blot聚丙烯酰胺凝胶电泳的基本原理及常见问题分析复习课程

聚丙烯酰胺凝胶电泳的基本原理及常见问题分析 聚丙烯酰胺凝胶电泳简称为PAGE(Polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis),是以聚丙烯酰胺凝胶作为支持介质的一种常用电泳技术。聚丙烯酰胺凝胶由单体丙烯酰胺和甲叉双丙烯酰胺聚合而成,聚合过程由自由基催化完成。催化聚合的常用方法有两种:化学聚合法和光聚合法。化学聚合以过硫酸铵(AP)为催化剂,以四甲基乙二胺(TEMED)为加速剂。在聚合过程中,TEMED催化过硫酸铵产生自由基,后者引发丙烯酰胺单体聚合,同时甲叉双丙烯酰胺与丙烯酰胺链间产生甲叉键交联,从而形成三维网状结构。 PAGE根据其有无浓缩效应,分为连续系统和不连续系统两大类,连续系统电泳体系中缓冲液pH值及凝胶浓度相同,带电颗粒在电场作用下,主要靠电荷和分子筛效应。不连续系统中由于缓冲液离子成分,pH,凝胶浓度及电位梯度的不连续性,带电颗粒在电场中泳动不仅有电荷效应,分子筛效应,还具有浓缩效应,因而其分离条带清晰度及分辨率均较前者佳。不连续体系由电极缓冲液、浓缩胶及分离胶所组成。浓缩胶是由AP催化聚合而成的大孔胶,凝胶缓冲液为pH6.7的Tris-HC1。分离胶是由AP催化聚合而成的小孔胶,凝胶缓冲液为pH8.9 Tris-HC1。电极缓冲液是pH8.3 Tris-甘氨酸缓冲液。2种孔径的凝胶、2种缓冲体系、3种pH值使不连续体系形成了凝胶孔径、pH值、缓冲液离子成分的不连续性,这是样品浓缩的主要因素。 蛋白质在聚丙烯酰胺凝胶中电泳时,它的迁移率取决于它所带净电荷以及分子的大小和形状等因素。如果加入一种试剂使电荷因素消除,那电泳迁移率就取决于分子的大小,就可以用电泳技术测定蛋白质的分子量。1967年,Shapiro等发现阴离子去污剂十二烷基硫酸钠(SDS)具有这种作用。当向蛋白质溶液中加入足够量SDS和巯基乙醇,SD S可使蛋白质分子中的二硫键还原。由于十二烷基硫酸根带负电,使各种蛋白质—SDS复合物都带上相同密度的负电荷,它的量大大超过了蛋白质分子原的电荷量,因而掩盖了不同种蛋白质间原有的电荷差别,SDS与蛋白质结合后,还可引起构象改变,蛋白质—SDS复合物形成近似“雪茄烟”形的长椭圆棒,不同蛋白质的SDS复合物的短轴长度都一样,约为1 8A,这样的蛋白质—SDS复合物,在凝胶中的迁移率,不再受蛋白质原的电荷和形状的影响,而取决于分子量的大小由于蛋白质-SDS复合物在单位长度上带有相等的电荷,所以它们以相等的迁移速度从浓缩胶进入分离胶,进入分离胶后,由于聚丙烯酰胺的分子筛作用,小分子的蛋白质可以容易的通过凝胶孔径,阻力小,迁移速度快;大分子蛋白质则受到较大的阻力而被滞后,这样蛋白质在电泳过程中就会根据其各自分子量的大小而被分离。因而S DS聚丙烯酰胺凝胶电泳可以用于测定蛋白质的分子量。当分子量在15KD到200KD之间时,蛋白质的迁移率和分子量的对数呈线性关系,符合下式:logMW=K-bX,式中:MW为分子量,X为迁移率,k、b均为常数,若将已知分子量的标准蛋白质的迁移率对分子量对数作图,可获得一条标准曲线,未知蛋白质在相同条件下进行电泳,根据它的电泳迁移率即可在标准曲线上求得分子量。 SDS-聚丙烯酰胺凝胶电泳经常应用于提纯过程中纯度的检测,纯化的蛋白质通常在SDS电泳上应只有一条带,但如果蛋白质是由不同的亚基组成的,它在电泳中可能会形成分别对应于各个亚基的几条带。SDS-聚丙烯酰胺凝胶电泳具有较高的灵敏度,一般只需要不到微克量级的蛋白质,而且通过电泳还可以同时得到关于分子量的情况,这些信息对于了解未知蛋白及设计提纯过程都是非常重要的。

wb注意事项

Western blot 注意事项 1.当进行接触滤纸、凝胶和膜的操作时,应戴手套。手上的油脂会阻断转移 2提蛋白一定要过硬,不能吝惜蛋白酶抑制剂 3测定蛋白浓度一定要选好方法 4. 最重要的,wb的成功最大程度的依赖于sds-page 5.最好有预染marker 6.底物显色的这一步也非常关键 7.蛋白质从SDS聚丙烯酰胺凝胶转移至硝酸纤维素膜(湿式转膜) 常见问题: 1、两快玻璃板之间灌胶,胶为什么总是不平? 1) 玻璃没有洗干净,应该要洗得非常干净! 2) 过硫酸铵和TEMED的加量不合适,加量相对较多,凝胶凝固过快也会胶不平,最多按照分子克隆加倍。 3) 加完试剂以后没有很好的摇匀,导致有些部位的聚合剂浓度过高,聚合相对较快造成胶不平。4) 稍微注意手法,均匀加入。5) 灌胶后应该用水或者正丁醇压胶面。6) 边缘胶是不容易聚合完全的,灌完胶后要立即加无水正丁醇覆盖,浓度越低的胶越不要使用双蒸水压顶,另外还可以在压顶试剂如正丁醇中添加少许AP来增加边缘胶的凝聚强度。7) 温度也是影响胶聚合的重要因素,可能为了让胶更快的凝固而把胶放到50度的温箱,由于受热不均匀,也会造成胶聚合不均匀。 2、胶为什么总是漏?1)每次电泳完后,洗净玻璃、胶条和其它附件。2)避免玻璃边缘(与胶条接触处)破损很重要,尤其是下面和胶条接触的地方。3)关键是找一块很平的桌面,使两块玻璃底面非常齐就行了。4)胶条一定要干,跑完电泳后,胶条就放在实验台上晾着。5)下面的胶条注意不要老化,如果有裂纹的话用保鲜膜垫在上面,也可以有效防止漏胶,或者反过来用6)玻璃在使用过程中容易造成小的缺口,从而导致封条无法完全密封,装好架子后,在玻璃底边上抹上一层薄薄的凡士林就好了,两边多点(容易从两边漏)这样就不会漏了,就算是用了很久的很多小缺口的玻璃都没有问题,然后转移到电泳槽的时候,去掉封条,把底上的凡士林擦干。(注意,一定要擦干净,尤其是少量进入了两隔玻璃之间空腔的,因为凡士林不导电,会影响电泳的效果。)7)可以在海绵垫下再垫一些纸,使得它与玻璃贴的更紧密。或者在玻璃底部用琼脂糖封上。8)因为两块玻板没有放的完全对齐,底部不在同一个平面,所以封条封不严,重新对齐后就不漏了。以后每次只要在水平的桌面上仔细对齐两块玻板,再夹紧。用手感觉一下确定在同一平面上后,放到灌胶架并压在封条上,卡紧。注意两边均匀用力,一般不会再漏。9)先把两块玻片放在夹子上,不要加紧,放到架子上,使两块玻片的底部对齐,夹紧两块玻片,然后取下再在其下面垫上垫片,这样一般就不会漏胶了。 3、条带跑得比正常的窄?1)可能因为胶凝的不均匀,聚合的不是很好,灌胶的时候尽量混匀. 2)可能与拔梳子有关,拔梳应该迅速,冲洗加样孔的时候要小心,以免把上样带扭曲;胶配好了用枪吹几下再灌胶,还有就是要等指示剂跑到两层胶交界成一线时,再调高电压。3)可能是样品的问题,如果盐浓度较高,便会挤压其它条带,致使条带宽窄不一,由于同样的原因,样品在凝胶中的速度会很慢,造成条带走的较慢。4)常见的原因是:每孔上样量不均匀,应确保每孔中上样量一致。5)可能是系统的ph出了问题,有可能是电极缓冲液,也有可能是凝胶缓冲液,更新缓冲液。 4、为什么会有“微笑”和“倒微笑”这样的效果呢?1)"微笑"是因为灌胶的时候冷却不均匀,中间部分冷却不好,导致凝胶中的分子有不同的迁移率所致。这种情况在较厚的凝胶以及垂直电泳时常常发生。“倒微笑“也称“皱眉”现象常常是由于垂直电泳时电泳槽的装置不合适引起的,特别是当凝胶和玻璃板组成的三明治底部有气泡或靠近隔片的凝胶聚合不完全便会产生这种现象2)书上说出现“微笑”是因为整个胶冷凝的不均匀,中间部分和两端受热不一样而致成了“倒微笑”可能是因为两端的胶凝的不好,加APS和TEMED后应该混合均匀。3)样品中盐浓度过高?点样量太多或每孔点样量不均匀?电泳电压不稳定或

相关文档

- WesternBlot基本原理过程及注意事项

- WB注意事项及常见问题

- Western blot实验步骤及注意事项

- WB原理及操作注意事项详解

- Western blot的原理、操作及注意事项之令狐采学创编

- westernblot详细图解

- WB的原理操作及注意事项

- WB试验注意事项微信

- WB注意事项

- Westernblot实验步骤及注意事项1(精)

- Western blot的原理、操作及注意事项

- Western blot实验步骤及注意事项(精)

- western_blot-注意事项+takara

- Western-Blot基本原理、过程及注意事项

- Westernblot实验步骤及注意事项1(精)

- Westernblot实验步骤及注意事项

- 最详细的WesternBlot过程步骤详解

- westernblot基本原理、过程及注意事项

- Western blot步骤与经验总结

- western试验步骤及注意事项